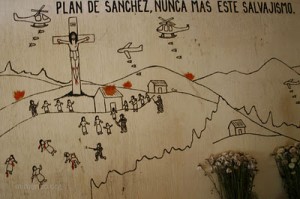

On July 18 th, 1982 armed forces, paramilitaries, and civil self-defense patrols (‘Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil’, or PACs) brutally massacred over 250 people in Plan de Sanchez, a remote Maya Achi community in northern Guatemala, outside of Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. The year of the massacre is considered one of the bloodiest of the internal armed conflict. Military officials frequently visited Plan de Sanchez to intimidate the local population and question about the whereabouts of men not involved with the PACs. Such presence created an environment of fear in which community members would sometimes hide in the hills nearby to avoid interaction with the military.

On July 18 th, 1982 armed forces, paramilitaries, and civil self-defense patrols (‘Patrullas de Autodefensa Civil’, or PACs) brutally massacred over 250 people in Plan de Sanchez, a remote Maya Achi community in northern Guatemala, outside of Rabinal, Baja Verapaz. The year of the massacre is considered one of the bloodiest of the internal armed conflict. Military officials frequently visited Plan de Sanchez to intimidate the local population and question about the whereabouts of men not involved with the PACs. Such presence created an environment of fear in which community members would sometimes hide in the hills nearby to avoid interaction with the military.

The PACs were one of the primary groups responsible for killings and disappearances throughout the armed conflict. The PAC program was initiated in 1982 by General Ríos Montt’s government with the intention of maintaining control over rural areas. The PACs were recruited and organized at the village level, where male community members were forced under threat of death or disappearance to serve without pay or remunerations of any kind. PACs were then forced to patrol their own neighbors and sometimes participate in kidnappings or murders within their communities. The PAC program was seen as a very important aspect of the military’s counterinsurgency and intelligence strategies.

The day of the massacre was a market day and many members of neighboring communities were passing through the village. In the early morning, witnesses report that two grenades fell east and west of Plan de Sanchez and by 2 or 3 pm, about 60 armed men in military uniforms arrived. Soldiers guarded all entry and exit points into or out of the community, while others went door to door gathering men, women, and children. The girls and young women were held separately, about 20 of which were taken to a house, raped, beaten and then killed. The remaining victims were put inside another house, which was then fired upon with guns and grenades and burned to the ground. Community members who arrived later that day discovered the house and bodies charred and still smoldering. Local PAC officers and community members were ordered to bury the bodies immediately in 21 mass graves.

The day of the massacre was a market day and many members of neighboring communities were passing through the village. In the early morning, witnesses report that two grenades fell east and west of Plan de Sanchez and by 2 or 3 pm, about 60 armed men in military uniforms arrived. Soldiers guarded all entry and exit points into or out of the community, while others went door to door gathering men, women, and children. The girls and young women were held separately, about 20 of which were taken to a house, raped, beaten and then killed. The remaining victims were put inside another house, which was then fired upon with guns and grenades and burned to the ground. Community members who arrived later that day discovered the house and bodies charred and still smoldering. Local PAC officers and community members were ordered to bury the bodies immediately in 21 mass graves.

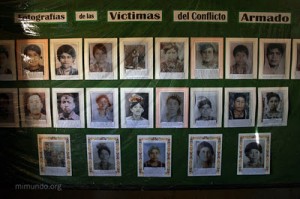

After threats and intimidation from local military officers, survivors from the community fled for several years. It wasn’t until 1993 that a group of community members was able to begin the process of seeking justice when they called upon the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office to denounce the massacre and have the bodies exhumed. In 1994, the Guatemalan Team of Forensic Anthropology (EAFG) dug up 19 sites in Plan de Sanchez, discovering the remains of at least 84 victims. The findings of their exhumation were not released until March 1995. In 1996, the Ombudsman’s office published a report on the massacres of Plan de Sanchez, Chichupac and Rio Negro, placing responsibility on state agents (mostly PACs), military commissioners, members of the army and high ranking officials for not protecting the community and trying to cover up the massacre. The report concluded that the massacres were part of a premeditated state policy — the ‘scorched earth’ campaign — ‘designed to defeat the insurgent movement through the strategic eradication of its civilian support base.’ Despite community and survivor efforts to initiate a government investigation into the case, little was done to respond to their requests and the Law of Reconciliation impeded those responsible from being charged.

After threats and intimidation from local military officers, survivors from the community fled for several years. It wasn’t until 1993 that a group of community members was able to begin the process of seeking justice when they called upon the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office to denounce the massacre and have the bodies exhumed. In 1994, the Guatemalan Team of Forensic Anthropology (EAFG) dug up 19 sites in Plan de Sanchez, discovering the remains of at least 84 victims. The findings of their exhumation were not released until March 1995. In 1996, the Ombudsman’s office published a report on the massacres of Plan de Sanchez, Chichupac and Rio Negro, placing responsibility on state agents (mostly PACs), military commissioners, members of the army and high ranking officials for not protecting the community and trying to cover up the massacre. The report concluded that the massacres were part of a premeditated state policy — the ‘scorched earth’ campaign — ‘designed to defeat the insurgent movement through the strategic eradication of its civilian support base.’ Despite community and survivor efforts to initiate a government investigation into the case, little was done to respond to their requests and the Law of Reconciliation impeded those responsible from being charged.

In a report put forward by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights, the Guatemalan State acknowledged that the massacre occurred and condemned the tragic loss of lives. The State also asserted that the massacre occurred in the context of the armed conflict and both sides experienced devastating losses. While the State recognized the gravity of the events, it also argued that it cannot be held responsible for examining the evidence or establishing a position, because such actions are delegated to the judiciary.

In 2004, the Inter-American Court on Human Rights finally reached a ruling on the case in which it argued that:

- There was genocide in Guatemala;

- The genocide was part of the framework of the internal armed conflict through the application of the National Security Doctrine in their counterinsurgency actions

- These counterinsurgency actions took place during the regime of General Efraín Ríos Montt

The ruling also stated the armed forces of the Guatemalan government had violated the following rights protected and delineated by the Human Rights Convention of the Organization of American States:

- The right to personal integrity

- The right to judicial protection

- The right to judicial guarantees of equality before the law

- The right to freedom of conscience

- The right to freedom of religion

- The right to private property

Furthermore, the Inter-American Court demanded that the Guatemalan government pay a reparations fee to the families of Plan de Sanchez of $25,000, which they paid in three installments. The government was also required to provide health care, mental health services, multicultural education, water systems, roads, and dignified housing. Finally, under the ruling, the government was to support and implement an investigation into the intellectual and material authors of the massacre, including former dictators Lucas García and Ríos Montt.

As of August of 2011, five people have been arrested and charged for their role in the Plan de Sanchez Massacre: Julian Acoj Morales, Lucas Tecu, Mario Acoj, Eusebio Grave, and Santos Rosales. The first four were arrested in early August 2011, all of whom denied any involvement in the massacre.

Read a detailed report on the case by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights here.