Published in El Quetzal Issue 14, May 2013

While the world watches the genocide trial in Guatemala, indigenous peoples and human rights defenders today are suffering persecution very similar to that perpetrated in the 1980s.

During the internal armed conflict, those who spoke out to defend their rights were systematically assassinated by the State. This violence was part of a government strategy that sought to maintain an economic system that benefited a small minority of elite families, leaving the indigenous majority in conditions of poverty. The State tried to justify its tactics by labeling these citizens as “internal enemies” who threatened Guatemala’s stability.

This violence and repression continues today. Activists who reject the government’s economic policies and demand that their vision of development be respected are again facing accusations of being internal enemies or terrorists. Some are victims of threats, assassination attempts, and extrajudicial executions, while others have been jailed under false criminal charges, becoming the nation’s first generation of political prisoners. Persecution comes not just from the State, but also from the private sector; national and multinational companies seeking to protect and expand investment opportunities, and their private security firm, many owned by former military officials, that act as the companies’ private armies.

Guatemala’s human rights situation has deteriorated since the beginning of 2013, and a series of recent attacks has caused alarm, both nationally and internationally.

The Guatemala Human Rights Defender Protection Unit (UEDEFEGUA) has registered 328 aggressions against defenders so far in 2013. Tragically, these acts rarely result in prosecution or even investigation, contributing to a dangerous environment of impunity.

In a recent statement, the Guatemala Human Rights Commission expressed “profound concern about this pattern of attacks against communities, their leaders and other human rights defenders.”

On the night of January 17, the main office of the Association for the Advancement of Social Sciences (AVANCSO) was broken into. This research center focuses on rural development, extractive industries, and historic memory. Unidentified persons sedated the security guard and then stole computers and important documents. The investigation by the authorities has not advanced.

On January 24, Daniel Pascual, leader of the Committee for Campesino Unity (CUC), and two representatives of Peace Brigades International were attacked and threatened on the road to San Antonio Las Trojes, San Juan Sacatepéquez. They were visiting to investigate a conflict generated by the construction of a well. Municipal authorities of San Juan Sacatepéquez accused Pascual and Peace Brigades of being destabilizing forces.

On February 25, Tomas Quej, leader of the community of Calihá, Alta Verapaz, left his community for Cobán after receiving a telephone call in which he was told to appear before the Cobán court. On February 28, he turned up dead from bullet wounds. Quej was a member of the People’s Council of Tezulutlán Manuel Tot, which works in defense of land rights. The case has not been solved.

On March 8, Carlos Antonio Hernández, union member and community leader, was assassinated by two men on a motorcycle. Days before the attack, he had received death threats in relation to his environmental activism in Camotán, Chiquimula. Hernández was also a member of the Camoteca Campesino Association, and the Executive Committee of the National Union of Guatemalan Health Workers

On March 15, Rubén Herrera, member of the Huehuetenango People’s Assembly for the Defense of Natural Resources (ADH) was detained. His detention occurred in the context of community opposition to a dam in Santa Cruz Barillas, Huehuetenango. The Public Prosecutor dismissed similar charges against 11 Barillas residents who were jailed for up to seven months before being released for lack of evidence.

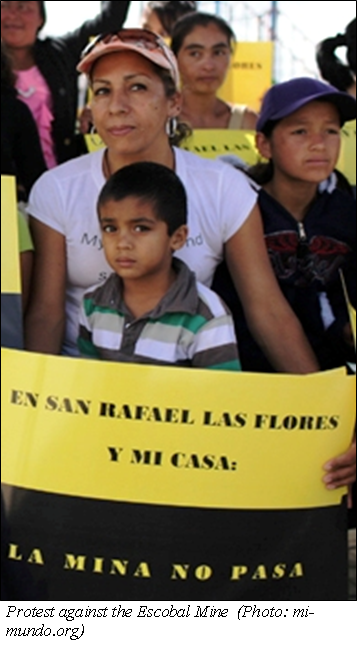

The night of March 17, four Xinca leaders from Santa María Xalapán were kidnapped while returning from a referendum in San Rafael Las Flores. Two of those detained escaped and one was released, but Exaltación Marcos Ucelo, Secretary of the Xinca Parlament, was found dead the next morning. The referendum was the most recent step in a two-year fight to oppose the Escobal Mine. Nevertheless, on April 3, the Guatemalan government approved the Canadian company Tahoe Resources’ license to mine gold and silver, without having concluded the investigation of the acts of violence or waiting for judicial rulings on the complaints filed by people who will be affected by the mine.

On April 8, Daniel Pedro, community leader from Santa Eulalia, was kidnapped in Santa Cruz Barillas. Pedro was also a member of ADH, and active in struggles against the hydroelectric dam in Barillas, as well as logging in Huehuetenango, which has displaced indigenous communities. His body was found on April 17.

On April 11, 26 community members were detained during a peaceful protest in San Rafael Las Flores, Cuilapa, Santa Rosa. They were protesting the approval of the license for the Escobal Mine. The protesters were on private property with permission from the owner yet security forces entered without a warrant. A number of men and women were injured by the tear gas used by the police during the arrests. On April 15, after giving their testimony, the charges against the 26 people were dropped and they were released.

On April 27, private security guarding the mine fired on protesters injuring 6. Though the Interior Minister tried to justify the guard’s actions, the head of mine security was arrested while trying to leave the country.

On May 2, a state of siege was declared in four municipalities in the departments of Jalapa and Santa Rosa around the Escobal Mine. The move suspended several constitutional rights and placed the army in command. Thousands of soldiers and police were sent to the area, dozens of houses were ransacked, and various people were arrested. Four of the arrested waited at least 18 days for their first hearing before a judge.

On May 2, a state of siege was declared in four municipalities in the departments of Jalapa and Santa Rosa around the Escobal Mine. The move suspended several constitutional rights and placed the army in command. Thousands of soldiers and police were sent to the area, dozens of houses were ransacked, and various people were arrested. Four of the arrested waited at least 18 days for their first hearing before a judge.

GHRC has called on authorities to do more to investigate cases of assassinations, threats, and attacks against human rights defenders and bring the perpetrators to justice. GHRC has also worked with a coalition of organizations to gather signatures calling for the release of Rubén Herrera and to deny the license for the Escobal Mine, and publically denounced the attacks on AVANCSO and Peace Brigades International. GHRC continues to urge the United States to do more to protect human rights defenders.

As Guatemala begins to chip away at impunity for egregious human rights violations of the past, we must ensure that cycles of repression and violence do not repeat against current-day activists working to create a more just and inclusive society.