| JUMP TO: Historic Overview >> Current Issues>> Related Cases >> Publications & Updates >> PROTECTIONS FOR LAND RIGHTS |

GHRC documents and denounces violations that arise from transnational extractive projects and other land conflicts and provides support in a number of paradigmatic cases.

Current land conflicts in Guatemala are in many ways rooted in the economic oppression and racism that dates back to the time of the Spanish conquest in the 1500s. The usurpation of indigenous lands — first by Spanish colonizers, then by an emerging group of Spanish-descent “elites,” then by foreigners encouraged to take over large tracts of land, and now to make way for large-scale development projects — has left a legacy of displacement, violence, torture and death.

Today, under both Guatemalan and international laws – including International Labor Organization Convention 169 and the Convention on Indigenous Peoples – indigenous peoples have a right to their ancestral lands, to be consulted about projects that will affect them as well as to decide what development will look like in their communities. Yet in direct violation of these obligations, the Guatemalan government has neglected to consult those affected by the imposition of megadevelopment projects.

In the absence of government consultation, communities have undertaken over 60 “good-faith” consultations – in which over 800,000 people have participated to date, the vast majority voting against dams and hydroelectric projects in their communities – yet Guatemalan courts have ruled the votes to be non-binding. Community groups and industry experts have also expressed significant environmental concerns, especially around the granting of mining licenses to companies that delivered incomplete or faulty environmental impact assessments.

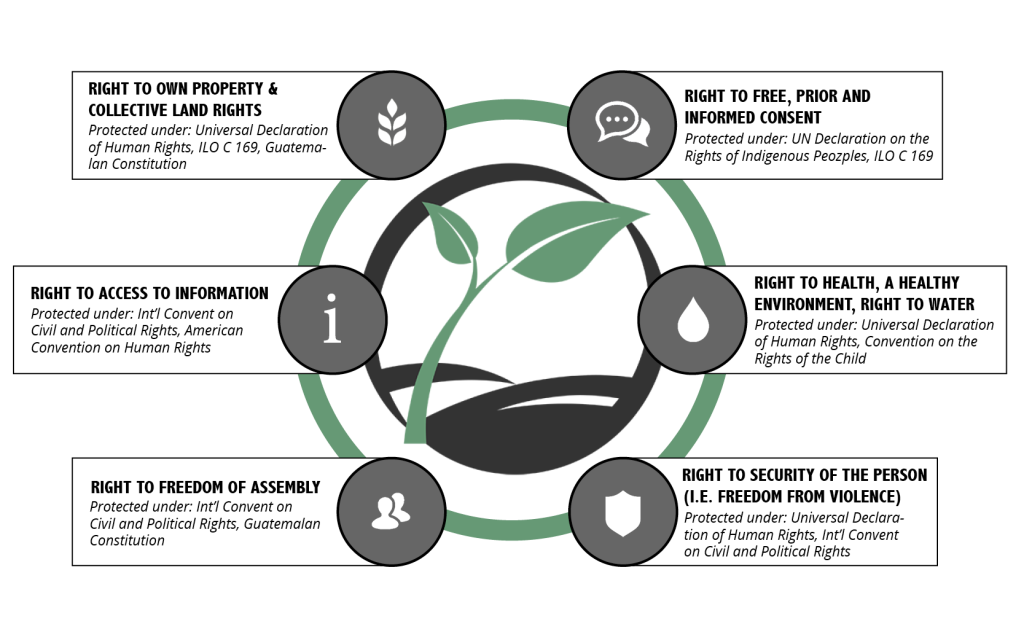

Some of the legal protections for indigenous communities and their lands are illustrated below:

Historic Overview: Land Conflict Ignites Coup and Internal Armed Conflict

In 1951, in the middle of Guatemala’s democratic “spring”, 70% of the land was owned by just 2% of the population. In order to promote a more democratic and equal society, President Jacobo Árbenz enacted a series of social reforms and a policy of modest land redistribution, including the purchase of fallow lands from large landowners. This effort lands owned by the US United Fruit Company (UFCO), which at the time owned huge tracks of land for banana cultivation — contributing to the country’s massive land inequalities.

Then Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, Allen Dulles, then Director of the CIA, both had strong ties to UFCO and lobbied for US intervention. In 1954 the CIA backed a coup against the Árbenz government using the threat of the expansion of communism in Latin America as justification. Most of the democratic reforms of the previous ten years were dismantled, ensuring that the Guatemalan oligarchy and international business interests could maintain their domination of arable land.

In the 36 year-long internal conflict that followed, millions of people were displaced and more than 200,000 people were murdered. The majority of those targeted by State forces were Mayan. As a result, many indigenous communities were forced to flee to the mountains, left landless, or left with small holdings in poorer soils.

Land Conflicts Today: New Waves of Displacement and Violence

The 1996 Peace Accords that ended the conflict acknowledged the importance of the right to recover lost land. A government fund, FONTIERRAS, was created to help redistribute land to indigenous groups and others affected by the war and to support those groups in the cultivation of the land. Unfortunately, the project was highly unsuccessful. The large landowners who invested in FONTIERRAS tended to sell low-quality land at unfairly high prices. Of the few farmers who obtained properties through the fund, many fell into debt and were eventually forced off their territories.

The historic inequalities surrounding land distribution in Guatemala have been further complicated by waves of land concessions to both national and transnational companies for large scale projects such as mines, hydroelectric dams, and monoculture agricultural crops. Over the past several years, the very same communities dispossessed and massacred during the war are finding themselves being evicted from their homes or resettled to make way for these projects, leading some community leaders to refer to this phenomenon as “economic genocide.”

Instead of spreading wealth and opportunity to the Guatemalan people, large scale projects — which continue to be promoted as a tool for economic opportunity — are contributing to the already massive assets of foreign companies, while causing local communities increased social and environmental degradation.

Those who attempt to organize against these massive projects — raising concerns about environmental contamination, lack of consultation and other rights violations — often suffer threats, public defamation, and violent repression. According to UDEFEGUA, the majority of attacks on human rights advocates during 2014 (82% of the total) were perpetrated against defenders of land and environmental rights. In coordination with the police and private security guards, the Guatemalan government has mobilized massive police and military forces to guarantee that “development” projects are not disrupted by local protests, often serving as de-facto private security for large companies.

In March 2015, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) heard several cases related to the presence of extractive industries in Latin America in a hearing on this topic. In October 2015, the IACHR held additional hearings on exrtractive industries, the right to water, and the effects of African Palm production. GHRC and many other Guatemalan and international civil society organizations continue to highlight the social and environmental costs of these projects, and support those engaged in the legitimate defense of their lands and the environment.

Related CasesEL ESTOR: RESISTANCE TO AN ILLEGAL NICKEL MINE The local Fisherman’s Guild and mayan Q’eqchi Authorities in El Estor united in October 2021 to form a resistance against the Fenix Mine, ruled to be illegally operating since 2005 by the Constitutional Court. With the impostion of a new consultation process that excluded impacted commuinties, the resistance formed to once again reject the mine and call for a free, fair, and inclusive consultation process. The resistance, however, has faced violence and intimidation from police, ading to the legacy of human rights violations associated with the mine. THE EL TAMBOR GOLD MINE (LA PUYA): Since 2010, the communities of San José del Golfo and San Pedro Ayampuc, just outside of Guatemala City, have denounced the imposition of a gold mine without community consent. Residents are concerned about the health and environmental impacts of the mine. GHRC has supported the resistance movement, known as La Puya, through advocacy, urgent actions, and direct support. Read GHRC’s report on the case here. THE POLOCHIC CASE: In a series of violent, forced evictions that took place starting in March 2011 to make way for a sugar refinery, almost 800 families from 12 communities were displaced in the Polochic Valley and left with nothing. During the eviction, two leaders were killed and entire communities lost their homes and belongings. Since then, only 140 families have been relocated, and many of them continue to live in poor conditions. GHRC continues to support the affected families as a petitioner on their behalf in the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which, since 2011, has maintained precautionary measures aimed to ensure that families receive the basic services they need. CAMBALAM DAM/ HYDROELECTRIC PROJECTS IN BARILLAS: Beginning in 2007, Mayan communities around the Cambalam River overwhelmingly began rejecting large-scale development projects, including the Cambalam Dam and other hydroelectroc projects. As a result of the resistance movement, a state of seige was declared in the region in 2012 and several community leaders were detained. Since then, several more land rights leaders from the department of Huehuetenango have been criminalized and detained. THE EL ESCOBAL SILVER MINE (SAN RAFAEL): Repression of social movements related to Tahoe Resources’ El Escobal silver mine in Guatemala has led to various conflicts, including the shooting of seven peaceful protesters by mine security in April 2013 and the death of a 16-year-old who had been active in organizing youth against the mine. Lawsuits against Tahoe are moving forward both in Canadian and in Guatemalan courts. A report by MadreSelva (summarized by NISGUA) on water quality at the Tahoe Mine found contamination of water by chemicals and metals. THE MARLIN MINE: The Marlin mine, an emblematic land rights case in Guatemala, is a project of Canadian mining giant Goldcorp which affects several Mayan (Mam) communities. A 2011 Tufts University report on the Marlin Mine concluded that the project poses significant environmental risks while providing “meager and short-lived” economic benefits to local communities. THE CEMENTOS PROGRESO CEMENT FACTORY (SAN JUAN SACATEPÉQUEZ): Towards the end of 2006, 12 communities joined together in resistance to the construction of a cement factory. Communities considered the government’s decision to grant the company a license an abuse, as residents were neither informed nor consulted about the project beforehand. Those on the front lines of the communities’ protests against the company have, for years, experienced aggression and defamation campaigns; a number of leaders have also been arrested. In the fall of 2014, martial law was declared in the region for about 45 days in response to a violent conflict related to the cement project. THE XALALA DAM: Thousands of indigenous people are fighting against the construction of the Xalala Dam, a hydroelectric project that would be built near the Chixoy River, downstream from the existing Chixoy Dam. |

|

Publications/Updates

|